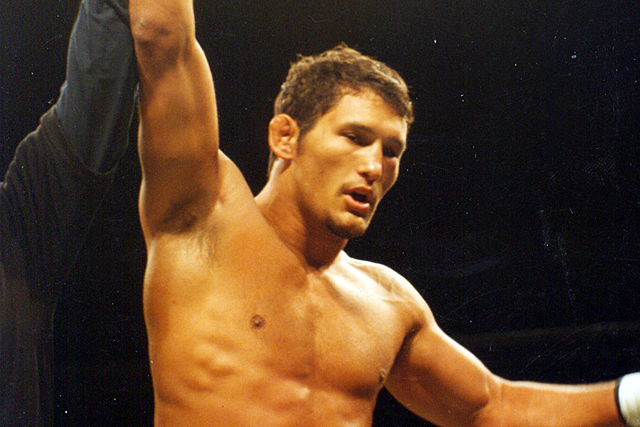

Vale Tudo Relics: The MMA Debut of Dan Henderson

Dan

Henderson launched his career in 1997. | Photo: Marcelo

Alonso/Sherdog.com

As he approaches his 45th birthday, Dan Henderson is firmly entrenched as one of MMA’s most beloved figures. During a historic career that spans nearly 18 years, the two-time Olympic wrestler has defeated some of the sport’s greatest competitors, from Fedor Emelianenko and Vitor Belfort to Wanderlei Silva and Mauricio Rua.

I had the honor of covering Henderson’s professional mixed martial arts debut at the Brazil Open ’97 on June 15, 1997 in Sao Paulo, Brazil.

Advertisement

Placed in the most difficult side of the bracket, Henderson first faced the favored Crezio de Souza, one of the most experienced and technical fighters from the Carlson Gracie Jiu-Jitsu team. The other semifinal pitted International Vale Tudo Championship titleholder Jose Landi-Jons against Hammer House representative Eric Smith. The crowd was not familiar with Henderson or Smith, so most expected an all-Brazilian final in the light heavyweight draw; Kevin Randleman and Tom Erikson were the favorites to meet in the heavyweight final.

With the Gracie team screaming de Souza’s name, a clearly nervous

Henderson climbed in the cage and was taken down by the Carlson

Gracie-trained black belt. Made up mostly of jiu-jitsu

practitioners, the crowd cheered as if its team had scored a goal.

De Souza immobilized “Hendo,” placed a knee on his belly and

mounted. Henderson quickly bucked and moved to the Rio de Janerio

native’s guard. From there, the American’s Olympic-level cardio

came into play, and his strikes began to land cleaner as he backed

de Souza against the fence. After a series of three hard punches,

referee Paulo Zorello made the correct call, stopped the fight 5:25

into the first round and awarded the technical knockout to the

American newcomer, much to the despair of Gracie’s pupils and every

jiu-jitsu representative in the building. They immediately set

aside their rivalries and joined forces in support of their art.

Gracie, Robson

Moura, Amaury

Bitetti, Fabio Gurgel,

Wallid

Ismail and Ricardo

Liborio all wanted to storm the ring and demand and explanation

from Zorello.

The pressure applied was so strong that the fight was almost restarted, but de Souza declined and thanked those in attendance for their support.

“It was a matter of honor,” he said. “This was an international event, and that kind of attitude would be frowned upon.”

Called in on short notice to replace Johil de Oliveira, who had been involved in car accident, Landi-Jons had issues with Smith’s takedowns. The American defended a couple of triangles and attempted armlocks to pound the Brazilian across 20 minutes for the decision victory.

In the first wrestler-versus-wrestler tournament final, Henderson wasted no time in submitting Randleman’s training partner. Smith went for a takedown, only to find himself caught in a fight-ending guillotine just 30 seconds into the match. Thus began the career of one of the most brilliant fighters of all-time.

Randleman met Erikson in the final of the heavyweight tournament. The Brazilian crowd was accustomed to seeing jiu-jitsu fighters refuse to fight each other in the finals of Brazilian jiu-jitsu events, so the fans assumed the all-wrestling final would result in something similar. However, as soon as the fight began, Randleman landed a shot to Erikson’s face, letting the crowd know it was in for a serious competition.

In a bid to follow up, Randleman clinched with his heavier opponent against the cage. Seeing a good opening, Erikson grabbed the back of his opponent’s head and landed a brutal right hook. Randleman was semi-conscious as he fell. Just to make sure, Erikson dropped down next to him and unleashed a flurry of blows that put the Mark Coleman disciple to sleep. Randleman was carried out on a stretcher, an oxygen mask attached to his head. Seeing doctors struggle to get Randleman on the stretcher, Erikson assisted in picking up his 231-pound countryman and earned the crowd’s admiration.

“That was a really tough fight,” Erikson said, “since Kevin is my friend and I train with Coleman at times.”

According to the Brazil Open promoter, it was difficult to find qualified Brazilian fighters willing to enter the heavyweight tournament in wake of Erikson’s bout with Murilo Bustamante at a Martial Arts Reality Superfighting show in Alabama seven months earlier. Therefore, he resorted to the 6-foot-3, 214-pound Silvio Vieira and the 6-foot-1, 216-pound Gustavo Homem de Neve. The decorated American wrestlers had no trouble steamrolling their way to the final. Erikson needed only 2:39 to take down and stop “Pantera Negra” with punches from the mount, and Randleman dropped de Neve with a straight punch and made him tap to vicious ground-and-pound before the three-minute mark.

Erikson and Randleman went on to success of their own in MMA, but Henderson blossomed into a superstar, becoming a two-division Pride Fighting Championships titlist. In the years to come, Henderson continued to carve the path that earned him the nickname “Brazilian’s Nightmare,” winning two more tournaments. In 1998, he earned decisions over Allan Goes and Carlos Newton to win the UFC 17 tournament; and two years later, he defeated Gilbert Yvel, Renato Sobral and Antonio Rodrigo Nogueira -- “Minotauro” later avenged the loss -- to win the seven-figure top prize at the Rings “King of Kings” tournament. Henderson was the smallest fighter to enter the open weight competition.

Henderson also knocked out Renzo Gracie at Pride 13, defeated Murilo Rua at Pride 17, beat Murilo Bustamante twice and avenged a loss to the aforementioned Silva with a violent knockout. The only other Brazilians to defeat him besides “The Axe Murderer” and “Minotauro” were Belfort, Ricardo Arona, Antonio Rogerio Nogueira and Anderson Silva.

Still active well into his 40s, Henderson has generated a resume that speaks for itself and serves as an example for athletes of every sporting background who see size and age as determining factors in success.

More

Marcelo Alonso’s MMA Roots Series

Marcelo Alonso’s MMA Roots Series