The Many Layers of Antonio McKee

The Many Layers

Todd Martin Dec 27, 2010

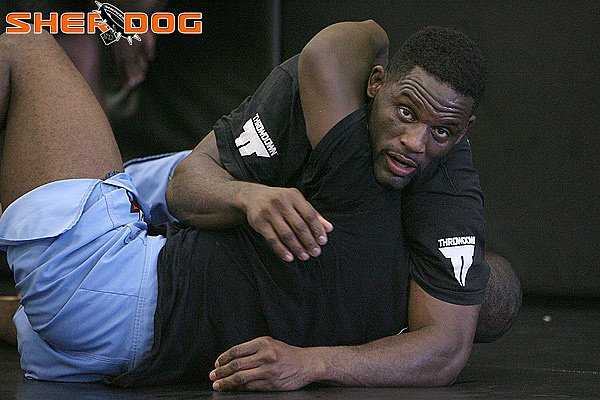

Antonio McKee | Dave Mandel/Sherdog.com

LONG BEACH, Calif. -- Antonio McKee is a man of contradictions.

A boy brought up amidst poverty and violence has grown into a man with an entrepreneurial instinct and comfortable lifestyle. A boisterous personality in front of the camera, McKee is a markedly different individual behind the scenes. Perhaps most strikingly, he is an athlete keenly aware of the style of fighting which sells tickets, yet one who has developed a reputation for one of the most conservative, inactive styles in the sport.

Advertisement

“I’m going to take them out one at a time,” McKee says of the lightweight division within the first five minutes of conversation. “Who’s going to beat McKee at 155? Only way I lose is if I’m not in shape or I get caught. Whose wrestling is better than mine? Gray Maynard? [Jacob] Volkmann? I’m going to make Volkmann look like nothing. We thought Volkmann could wrestle. Volkmann can’t wrestle.”

McKee often speaks of himself in the third person. And, as if his

boasts are not bold enough, McKee ups the ante in short order.

“I feel like I’m the Muhammad Ali of MMA,” he says. “I feel like I’m the Don King of MMA. I feel like I’m the Tupac Shakur of MMA. I’m the mouth, the talent, the brains, and I’m also the business side. Where does that put me? That puts me as one of the all-time greatest black mixed martial arts fighters.”

This is Antonio McKee in a sense: brash, cocky, an aggressive self-promoter. But dig a little deeper, and it is not Antonio McKee at all.

Over the course of a two-hour conversation, McKee discusses his philosophy on fighting and his take on the business of MMA. He delves into the realms of political science and history. By the end, a completely different McKee emerges. He is relaxed, and the bluster has vanished.

‘Controversy Sells’

Meili, McKee’s quiet young daughter, falls asleep on his lap. The news is muted on the flat-screen television. The family’s pet rabbit, Sassy B., hops around the room. McKee, after a life of turmoil and violence, seems at peace.

“A lot of times when people interview me, they provoke me to say the things that I say,” McKee admits, “and I know they’re doing it, so I play the game. That’s why I’m one of the most interviewed fighters in the game. I create controversy, and controversy sells.”

File Photo

McKee will make his Octagon

Debut against Volkmann (above).

A turbulent childhood shaped him. As his mother struggled with drug addiction, McKee had to take care of himself. He was surrounded by gangsters and drug dealers. A victim of molestation, McKee built up an inner anger that frequently raged to the surface. It is a past he is willing to discuss but only on the surface.

As a teenager, McKee found himself in and out of jail; it was wrestling that turned around his life. McKee began devoting large chunks of his free time to wrestling and excelled at the sport. Initially, his anger was still there. He got into fights during wrestling meets, but, over time, he matured.

McKee developed business interests and suppressed his inner anger. By the time he entered into MMA, he was a different person. Fighting was not an outlet for violence but rather a path to greater security. In addition to his fighting career, McKee engaged in a variety of entrepreneurial ventures. He opened a security company and a gym. He invested in real estate.

Today, McKee lives in Long Beach, not far from the dangerous territory where he grew up. However, he now resides in a nice neighborhood, with an apartment near the ocean. Identification is required not only to enter his luxury apartment building but also to use the elevator. His apartment has the polished and well-kept look of a white-collar professional.

It is the classic American story of a kid from a rough background making good. Ironically, as a fighter, McKee has been criticized for essentially not being violent enough.

Violent Motivations

MMA is a violent sport -- an inescapable reality for anyone who follows it closely but particularly obvious to the participants. That truth is even more striking to a competitor who has spent much of his life trying to move away from violence.

“Is there someone you love?” McKee asks, rhetorically. “Let’s say they’re a fighter and they’re going to face [Quinton] ‘Rampage’ [Jackson] or Chuck Liddell. When you’re watching that guy knock your loved one out, split them open, choke them unconscious, how does that make you feel as a person?

“All of a sudden you have feelings, because that’s someone you care about. Well, I care about the safety of all fighters,” he adds. “I don’t want to beat a person up to where they’re split open, because somebody loves that person. [Luciano] Azevedo got staples in his head. He’ll never be able to take that scar away, and he was just working, trying to make some money. It hurts me to do that to people, but I can see what the crowd wants.”

Pleasing the crowd has not been a hallmark of McKee’s MMA career.

In early 2010, at nearly 40 years of age, McKee recognized that his window of opportunity in the sport was rapidly closing. He had not lost since 2003, but the UFC wasn’t calling. McKee had developed a reputation as a fighter who would take down his opponents, hold them there and secure safe decision wins.

McKee fights at 155 pounds, a division where speed, reflexes and conditioning are of paramount importance. Once-dominant fighters such as Jens Pulver, Yves Edwards and Rumina Sato have faded at young ages; it is not the domain of the older man.

“

I feel like I’m

the Muhammad Ali

of MMA ... I’m

the mouth, the

talent, the brains,

and I’m also the

business side.

”

Mezger, the fighter-turned-commentator for HDNet, called McKee’s fights in Canada’s Maximum Fighting Championship and directed pointed criticisms at McKee’s style of fighting. McKee was accustomed to fans’ denigration, but it was jarring to hear it coming from someone who was supposed to be generating interest in his fights.

“He said the truth, but it wasn’t the fact he said the truth. It was the way he said it. As a professional spokesman for a show, I thought your job would be to uplift me as a fighter and make me sound good,” McKee says. “As a commentator, I didn’t understand the negativity he was putting out on a fighter. I’ve never once heard the UFC do something like that. But, Guy Mezger saying what he said made me realize what I needed to do.”

Following victories over Carlo Prater and Derrick Noble in 2009, McKee asked UFC matchmaker Joe Silva what the UFC wanted to see from him in order to eventually be given an opportunity with the organization. Silva told him to finish some fights. In turn, McKee recorded a first-round submission of Rodrigo Ruiz in his next outing. He went a step further for the following bout.

Continue Reading » Page Two: An Answer Approaches

Related Articles