How the Mighty Have Fallen

Tim Leidecker Nov 4, 2008

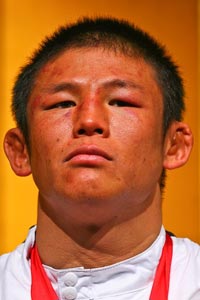

When former Pride lightweight champion Takanori

Gomi succumbed to Marcus

Aurelio’s arm-triangle choke in April 2006, it sent a shockwave

of surprise through the MMA community.

When Gomi was submitted by Nick Diaz 10 months later, the general reaction was overwhelming.

But after unrenowned Russian kickboxer Sergey

Golyaev outpointed him last Saturday, the majority of fans and

experts just shrugged their shoulders as if to say, “Yeah,

whatever.”

Even though the 30-year-old knockout artist had lost his aura of invincibility before Japanese promotion Dream Stage Entertainment made him one of the “aces” of its Bushido series, which was designed to showcase the lighter weight classes, Gomi thrilled the crowds from Tokyo to Yokohama, from Nagoya to Osaka with his strong wrestling, explosive punching and aggressive fighting style.

Gomi had appeared to be en route to his second straight unanimous decision against the unheralded Russian. Late in the first round, he had threatened with an armbar attempt, though Golyaev was saved by the bell. For seven minutes and 42 seconds, it was another day at the office for Gomi, until a left hook caught him right on the button and sent him into survival mode. The punch and a brief portion of ground-and-pound had the former champion backpedaling for the rest of the round.

While the third round was all Gomi, who scored with stomp kicks and rained down punches from the mount, it was not until the final minute of the stanza that he really came to life and punched with the intention of knocking the Russian out. In the end, however, he had to swallow a split decision loss that would not have materialized under the Unified Rules. According to Sengoku’s judging criteria, though, the decision was perfectly reasonable because Golyaev, while doing not much else, came closest to finishing the bout at one point.

What’s harder to explain is Gomi’s sudden drop in form.

Sure, he had to take a full year off from fighting after the sale of Pride to Zuffa, when he was locked out on a contract dispute. But following the three hard rounds against Seung Hwan Bang in August, the ring rust should have come off. The possibility that Gomi is already beyond his best sporting days can also be ruled out simply because he is still in his prime physically.

The most reasonable explanation might be that the burden of being the main draw for the upstart promotion -- in addition to Kazuo Misaki and the occasional Hidehiko Yoshida appearance -- is simply putting too much pressure on the 155-pounder’s small shoulders. In Pride Bushido he had a core support group of strong second stringers like Gono, Minowa, Sakurai and Chonan to entertain the crowd. Now Gomi needs to put on a show for the fans who expect him to shine and win as he did in his Pride heyday, which can lead to him forgetting fundamentals and losing fights he was supposed to win.

Kitaoka poses litmus test for Gomi

Gomi’s Jan. 4 bout against rising star Satoru Kitaoka will be crucial to see where his career is headed. Last time Gomi was threatened by a Japanese challenger, he emphatically finished off Mitsuhiro Ishida -- a fighter similar to Kitaoka in build and style -- with a soccer kick and punches in 1:14.

Can Kitaoka, whose brash statements before and after Sengoku 6 have certainly angered the longtime king of the lightweight division, light a competitive fire under Gomi again?

From a sporting perspective, the 5-foot-6 grappling wizard has done his homework. Kitaoka coasted through the Sengoku lightweight tournament, finishing all of his opponents inside the first round except for fellow finalist Kazunori Yokota. His strongest asset is his wrestling, as evidenced by his explosive double-leg takedown that’s arguably the best of any Japanese fighter today. The seven-year Pancrase veteran also attacks the limbs of his opponents in the fashion of a 2004 Ryo Chonan.

The tournament victory brings some late recognition for the 28-year-old, who holds wins over a trio of titleholders -- Deep champion Hidehiko Hasegawa, WEC champion Carlos Condit and Cage Rage champion Paul Daley -- but never managed to put the gold around his own waist.

What’s particularly remarkable about Kitaoka is the fact that he has competed as high as the old Pancrase middleweight (181-pound) division when he could effectively fight as a featherweight given his size. Despite cutting in excess of 30 pounds for the tournament finals, the Nara native still sported arms that were a match for those of Sean Sherk and thighs that even eclipse those of Tyson Griffin.

Misaki a tough matchup for Santiago

In the end Kitaoka pocketed a cool 5,000,000 yen (around $50,000) for his efforts, as did the middleweight grand prix champion Jorge Santiago. The Brazilian, whose mixed martial arts career was born and bred at talent hotbed American Top Team in southern Florida, had an arguably even tougher route to the title. He had to go through durable American Logan Clark, Shooto light heavyweight champion Siyar Bahadurzada and former Pride gatekeeper Kazuhiro Nakamura.

The well-rounded Rio de Janeiro native, who seems to have a knack for fighting more than once in a night after already winning the Strikeforce middleweight tournament last year, achieved two novelties besides taking the tourney: He became the first man to submit Clark as well as the first middleweight to knock out the experienced judo player Nakamura.

Looming on the horizon for Santiago is a Jan. 4 clash with Bushido grand prix champion Kazuo Misaki for the vacant middleweight strap. Not only is the “Grabaka Hitman” the most high-profile opponent Sengoku can offer Santiago at this time, he is also the type of fighter that has given him the most difficulty in his career. Looking at his track record, Santiago has lost to Alan Belcher, Chris Leben and Joey Villasenor -- all fighters who are blessed with above-average kickboxing skills, as is Misaki.

Regardless of how this bout will play out or whether the promotion’s first middleweight champion will hail from Japan or Brazil, Sengoku has to continue trying to build both native and foreign stars. Because the history of Japanese MMA has shown that for every Takada, there has to be a Rickson. For every Sakuraba, there has to be a Wanderlei Silva. And for every Yoshida, there has to be a Cro Cop.

When Gomi was submitted by Nick Diaz 10 months later, the general reaction was overwhelming.

Advertisement

Even though the 30-year-old knockout artist had lost his aura of invincibility before Japanese promotion Dream Stage Entertainment made him one of the “aces” of its Bushido series, which was designed to showcase the lighter weight classes, Gomi thrilled the crowds from Tokyo to Yokohama, from Nagoya to Osaka with his strong wrestling, explosive punching and aggressive fighting style.

Little of that is left in the 2008 version of Gomi, who is supposed

to be one of the cornerstones for fledging promotion World Victory

Road. His first two outings in Sengoku -- wins over American

Duane

Ludwig in March and Korean Seung Hwan

Bang in August -- were solid but unspectacular. In the end, the

successful outcomes may have diverted from the fact that the spark

of former days is gone.

Gomi had appeared to be en route to his second straight unanimous decision against the unheralded Russian. Late in the first round, he had threatened with an armbar attempt, though Golyaev was saved by the bell. For seven minutes and 42 seconds, it was another day at the office for Gomi, until a left hook caught him right on the button and sent him into survival mode. The punch and a brief portion of ground-and-pound had the former champion backpedaling for the rest of the round.

While the third round was all Gomi, who scored with stomp kicks and rained down punches from the mount, it was not until the final minute of the stanza that he really came to life and punched with the intention of knocking the Russian out. In the end, however, he had to swallow a split decision loss that would not have materialized under the Unified Rules. According to Sengoku’s judging criteria, though, the decision was perfectly reasonable because Golyaev, while doing not much else, came closest to finishing the bout at one point.

What’s harder to explain is Gomi’s sudden drop in form.

Sure, he had to take a full year off from fighting after the sale of Pride to Zuffa, when he was locked out on a contract dispute. But following the three hard rounds against Seung Hwan Bang in August, the ring rust should have come off. The possibility that Gomi is already beyond his best sporting days can also be ruled out simply because he is still in his prime physically.

The most reasonable explanation might be that the burden of being the main draw for the upstart promotion -- in addition to Kazuo Misaki and the occasional Hidehiko Yoshida appearance -- is simply putting too much pressure on the 155-pounder’s small shoulders. In Pride Bushido he had a core support group of strong second stringers like Gono, Minowa, Sakurai and Chonan to entertain the crowd. Now Gomi needs to put on a show for the fans who expect him to shine and win as he did in his Pride heyday, which can lead to him forgetting fundamentals and losing fights he was supposed to win.

Kitaoka poses litmus test for Gomi

Gomi’s Jan. 4 bout against rising star Satoru Kitaoka will be crucial to see where his career is headed. Last time Gomi was threatened by a Japanese challenger, he emphatically finished off Mitsuhiro Ishida -- a fighter similar to Kitaoka in build and style -- with a soccer kick and punches in 1:14.

Can Kitaoka, whose brash statements before and after Sengoku 6 have certainly angered the longtime king of the lightweight division, light a competitive fire under Gomi again?

From a sporting perspective, the 5-foot-6 grappling wizard has done his homework. Kitaoka coasted through the Sengoku lightweight tournament, finishing all of his opponents inside the first round except for fellow finalist Kazunori Yokota. His strongest asset is his wrestling, as evidenced by his explosive double-leg takedown that’s arguably the best of any Japanese fighter today. The seven-year Pancrase veteran also attacks the limbs of his opponents in the fashion of a 2004 Ryo Chonan.

The tournament victory brings some late recognition for the 28-year-old, who holds wins over a trio of titleholders -- Deep champion Hidehiko Hasegawa, WEC champion Carlos Condit and Cage Rage champion Paul Daley -- but never managed to put the gold around his own waist.

What’s particularly remarkable about Kitaoka is the fact that he has competed as high as the old Pancrase middleweight (181-pound) division when he could effectively fight as a featherweight given his size. Despite cutting in excess of 30 pounds for the tournament finals, the Nara native still sported arms that were a match for those of Sean Sherk and thighs that even eclipse those of Tyson Griffin.

Misaki a tough matchup for Santiago

In the end Kitaoka pocketed a cool 5,000,000 yen (around $50,000) for his efforts, as did the middleweight grand prix champion Jorge Santiago. The Brazilian, whose mixed martial arts career was born and bred at talent hotbed American Top Team in southern Florida, had an arguably even tougher route to the title. He had to go through durable American Logan Clark, Shooto light heavyweight champion Siyar Bahadurzada and former Pride gatekeeper Kazuhiro Nakamura.

The well-rounded Rio de Janeiro native, who seems to have a knack for fighting more than once in a night after already winning the Strikeforce middleweight tournament last year, achieved two novelties besides taking the tourney: He became the first man to submit Clark as well as the first middleweight to knock out the experienced judo player Nakamura.

Looming on the horizon for Santiago is a Jan. 4 clash with Bushido grand prix champion Kazuo Misaki for the vacant middleweight strap. Not only is the “Grabaka Hitman” the most high-profile opponent Sengoku can offer Santiago at this time, he is also the type of fighter that has given him the most difficulty in his career. Looking at his track record, Santiago has lost to Alan Belcher, Chris Leben and Joey Villasenor -- all fighters who are blessed with above-average kickboxing skills, as is Misaki.

Regardless of how this bout will play out or whether the promotion’s first middleweight champion will hail from Japan or Brazil, Sengoku has to continue trying to build both native and foreign stars. Because the history of Japanese MMA has shown that for every Takada, there has to be a Rickson. For every Sakuraba, there has to be a Wanderlei Silva. And for every Yoshida, there has to be a Cro Cop.

Related Articles