Fighting on a Prayer

Fighting on a Prayer

Jack Encarnacao Nov 11, 2010

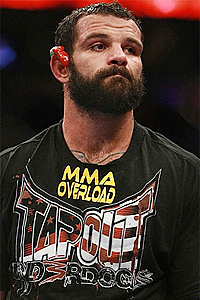

Jorge Rivera (top): Dave Mandel | Sherdog.com

BOSTON -- The first time Jorge Rivera remembers teetering on the brink of forfeit was in a jail cell near Beantown. It was about 1995, and he had not yet stepped into a fight gym. He did his fighting in the streets or in barrooms. In defiance of his loved ones, not for them.

Advertisement

“After every fight, I always thank God because that’s the promise I made to him,” he adds. “I’ve gone through my bouts with my beliefs where I don’t know what I believe anymore. I’m going to keep my word. I promised him I would do that.”

Most stories like these feature a moment in which a man hits rock

bottom before bouncing back. For Rivera, the jail cell scene would

be a classic example, perhaps the opening scene in a movie about

his life.

However, he has had several rock bottoms: jail stints, a divorce, a jaw-breaking knockout loss, the death of his teen-aged daughter. He has been broke, stressed and depressed. His arm, joints and heart have all been broken. Somehow, enough good still happens to keep him under the bright lights of the Ultimate Fighting Championship.

Throughout Rivera’s life, it’s as if he has needed to walk up to the brink before coming through. His signature UFC wins came after sound losses, losses that, dating back to when Lee Murray submitted him in 2004, signaled his days as a competitive UFC fighter were over.

File Photo

“I’m not worried about s--t,” Rivera says. “This is the one time that I can honestly say that if I get beat, Sakara’s a better man, he’s just a better fighter than I am, he deserves it more than I do. The truth is I’m not sick, I’m not hurt. I’m in good shape.”

Finally.

Rock Bottoms

After the jail cell prayer, Rivera began building a fight career, first on sparsely documented New England shows, including a 1999 decision win over Tim Sylvia. The money was not good. In 2002, he was in the middle of a divorce and sick as a dog when he faced Brazilian jiu-jitsu black belt Travis Lutter.

He was “flat broke” and had little other than stress to show for his fighting pursuits. He got on his hands and knees again.

“I’m like, ‘If I lose this fight, this is a sign that this is not meant to be,’” says Rivera, who stopped Lutter with strikes in the third round of a wild battle. “After that fight, I was so sick; I was throwing up all over the back. They had to hold me up.”

Four years later, Rivera faced another potential rock bottom. Coming off a deflating loss as a cast member on Season 4 of “The Ultimate Fighter,” he decided his UFC career, which started at UFC 44 in 2003, would be over if he lost again.

“I go to the house, I don’t win, I don’t make it to the finals, I’m thinking that this is the end of it,” Rivera says, recalling his thoughts before he stopped Edwin Dewees in November 2006.

He locked himself in his house as the reality show aired on television, afraid of how he would be perceived if producers spotlighted some of the emotional outpourings he had during filming. Rivera found himself telling cameras things about his rough-and-tumble formative years that he could never tell his parents for fear of breaking down.

However, he did not come off as bad as he expected -- his donning a clown suit and mocking Shonie Carter as “Phony Carter” is perhaps what is best remembered -- and he won his fight with Dewees at the season finale. Another rock bottom averted.

When one really looks at it, Rivera has had a remarkable run. Besides finalists Matt Serra and Chris Lytle, he is the only cast member from Season 4 of “The Ultimate Fighter” still under UFC employ. A crushing loss to Terry Martin at UFC 67 saw his jaw broken and Rivera again on the brink of being cut, but he knocked out Kendall Grove to stay alive. He tapped to Martin Kampmann at UFC 85, only to bounce back improbably with three straight wins.

“

envelope to the

line; that’s how I

am with everything.

”

Rivera’s father was an orphan. The Guayama, Puerto Rico, native lost his mother at an early age and then lost an older brother who had become the family caretaker. He came to America with no money in the late 1960s and met Jorge’s mother, also a Puerto Rican immigrant, in Massachusetts. He provided for Jorge and his brother, exercised tough love -- “He didn’t spare the rod,” Jorge says -- and stressed pride in their Puerto Rican heritage.

All the more reason why Rivera felt like a failure as he got wrapped up in local crime, a history from which he does not shy away and about which he does not reveal many details before stopping himself. He had trouble keeping a job then, ironic considering his staying power in the sometimes cutthroat UFC ranks. Rivera admits he has problems taking orders from someone behind a desk, or someone he does not respect. He described his mindset this way: if he had 20 sick days, he was taking 20 sick days.

“A lot of the things that I’ve done, he never gave us that example, he gave us the exact opposite,” Rivera says of his father, who today lives in Florida. “Work hard, be a good person. My brother and I, for a while, we were the exact opposite. We were kids from the streets.”

Related Articles